Error vs. Deception: Unpacking the 'Why' of Retractions (part 2/2)

A look into the applications of the retraction reasons taxonomy 2.0.

Over 50% of retractions include flaws in the science itself – errors in data, results, or methods. That part isn’t shocking. Research, by definition, explores the unknown and sometimes goes wrong. Over half of the retraction reasons have a noted problem with the research.

But here’s the more interesting question: Which papers were retracted only because of problems with the research itself? A bit under 9%. Those cases likely represent honest errors, not misconduct. They’re corrections, not indictments. And they matter because they show the system working as intended. But then there are papers retracted with a mention of apparent intent to deceive. This points to deeper issues in the research ecosystem: manipulation, misrepresentation, or misconduct.

The point to be made is that nuance matters when understanding when science works properly and when it doesn’t.

Building on Part 1, where I introduced the Taxonomy of Retraction Reasons 2.0 I look a bit more at the numbers and uses of the taxonomy.

It’s important to remember: most retraction notices cite multiple reasons. Rarely is a paper retracted for a single, simple cause. Retraction Watch, the primary source of these reasons, maintains an informative FAQ for anyone unfamiliar with how their curation works.

Sample Retractions and How the Taxonomy Provides Further Context

Let’s look at two examples:

‘Arsenic Life’

The recent retraction of the “arsenic life” paper is a good example of how flawed research, not misconduct, can lead to a retraction. In this case, the issue was apparent contamination of the microbes under study. The authors disagreed with the decision of retraction and stood by their conclusions. But Science editors retracted the paper anyway, stating that its conclusions were no longer supported by the data. Their retraction policy has evolved to include this kind of case, even when there’s no evidence of fraud.

As stated in Science’s retraction notice, their definition of why a paper is retracted has evolved. “If the editors determine that a paper’s reported experiments do not support its key conclusions, even if no fraud or manipulation occurred, a retraction is considered appropriate.” What is stated here is that their definitions for retractions have evolved, meaning we desperately need more tags (metadata) to qualify retractions.

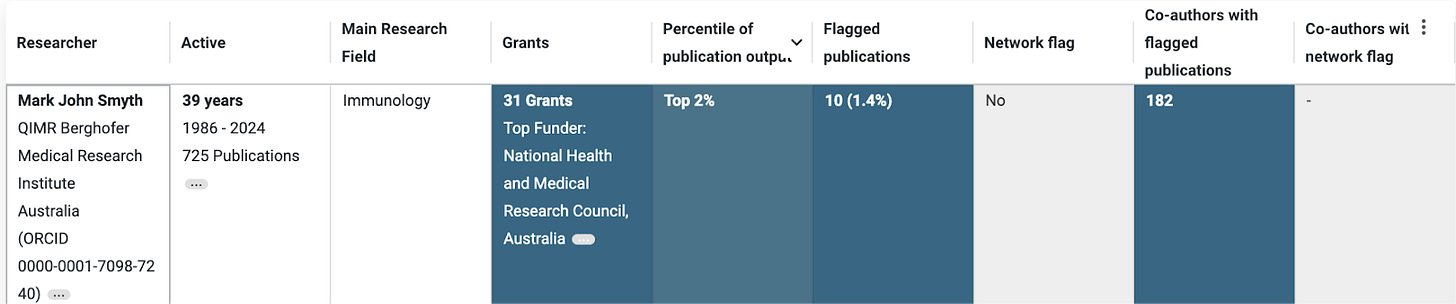

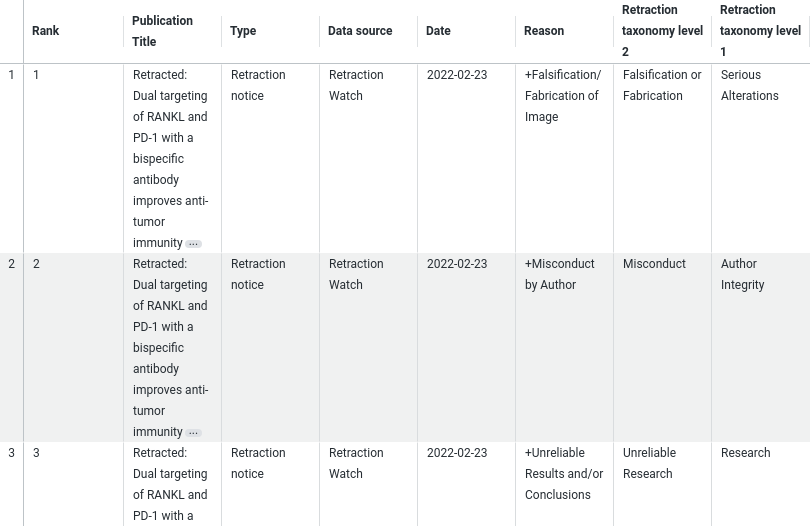

Mark Smyth Nelistotug Cancer Scandal

Dr Mark Smyth is back in the Australian news due to a national debate on how to better investigate allegations of misconduct (see these (paywalled) news articles here, here, and here).

What can be learned from his profile? He has a lot of publications (declining number since 2020), with 10 flagged publications and 182 co-authors affected by those flagged publications.

If we dive into one of the flagged publications, we can immediately see at Retraction Taxonomy Level 1 that there are issues with Serious Alterations, Author Integrity, and the Research. This means there aren’t just ‘honest errors’ in this research.

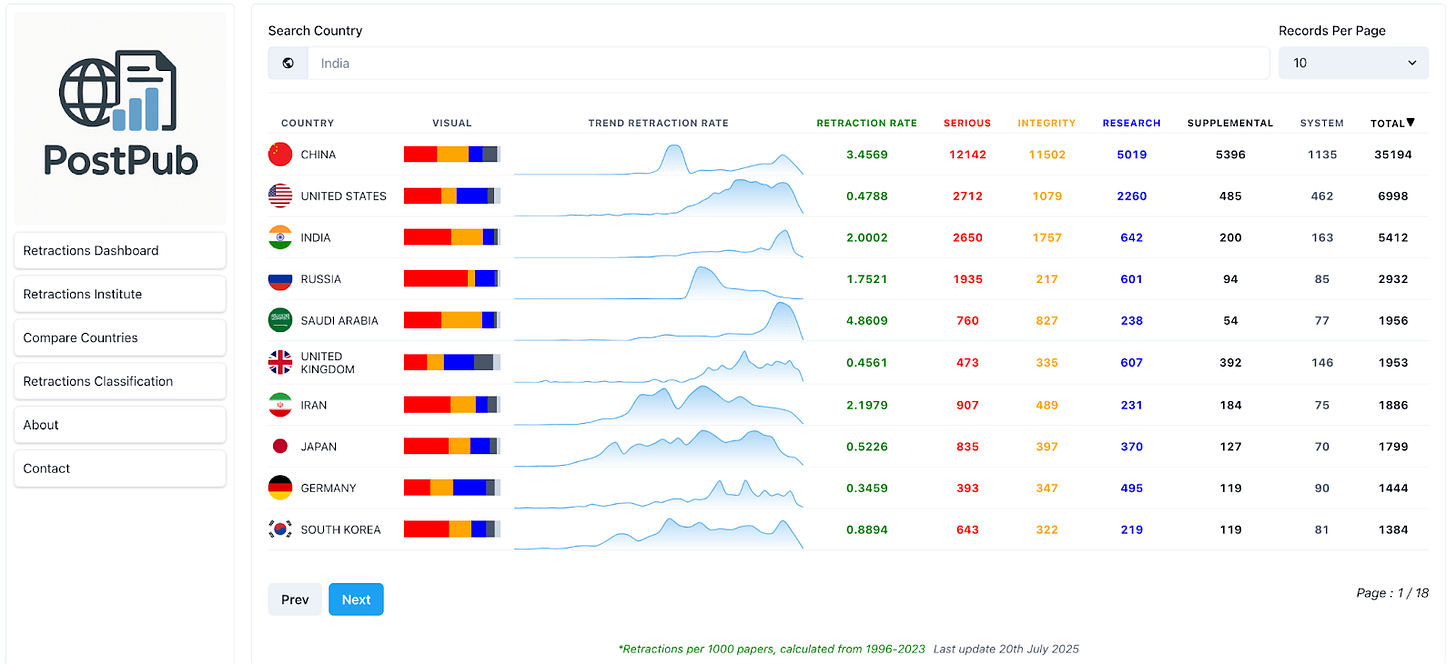

The Taxonomy in Practice: PostPub

The taxonomy isn’t just a theoretical framework — it’s already being used in the community. One of the first to incorporate it into a live platform was Achal Agrawal and team, who have been working on retractions and their implications in the Indian research ecosystem.

After we shared the initial version of the taxonomy, Achal applied it to a public dashboard. The project - now PostPub - has since evolved with multiple sources of support (including a Catalyst Grant from Digital Science in late 2024). PostPub now integrates taxonomy-informed tagging to surface patterns in retraction activity.

What makes this work notable is how it allows users to go beyond simple retraction counts. For example, you can easily identify which country has the most retractions, but more importantly, you can start to explore why those papers were retracted. That added layer of nuance is what the taxonomy is designed to support.

Achal has also been an active contributor to the taxonomy itself, offering valuable community feedback throughout its development, from version 1.0 to 2.0.

Final Thoughts

Should flawed research be retracted? That is a good question for the community to answer. From my point of view, at this time, there needs to be some tag on the paper as one shouldn’t trust the research as valid. Yet, the research community can and should learn a lot from flawed studies. These are a few examples:

The recent retraction of the ‘Arsenic Life' paper offers a valuable lesson in contamination – a common, frustrating, and instructive part of research. There will invariably be many more lessons to be learned from this case as time goes on.

In 2009, researchers famously placed a dead salmon in an fMRI scanner and showed it photos of people. Surprisingly, the scan showed “brain activity.” The point wasn’t that the fish was thinking; it was to highlight how fMRI studies can produce false positives if statistical corrections aren’t properly applied. This quirky experiment quickly became a symbol in neuroimaging of the importance of rigorous statistical practices.

Pre-prints - should there be retractions on these? If you retract them, that elevates their status to more than what they are. So, currently, I don’t think ‘retraction’ is appropriate. However, there are clear differences between repositories and preprint servers, and each preprint platform varies in its curation efforts. Should there be more transparency of these platforms’ policies on curation and acceptance? Yes.

As always, I’m grateful to others who help. In this case, thanks go to Mihaela-Alina Coste, who worked with me to transport old R code into Python and a Collab Notebook.