The Domino Effect of Faulty Metadata

Why Open Source Analysis Demands Metadata Vigilance

Scientific integrity doesn’t end with peer-reviewed results or reproducible methods. In the age of open infrastructure, metadata plays an increasingly critical role, not just in discoverability but in the traceability and attribution of research products. While it’s common knowledge that metadata perfection is unattainable, recent high-profile cases demonstrate that accepting imprecision without proactive governance can undermine research institutions, distort evaluations, and amplify misinformation.

In “transparent” open science environments (and pipelines), errors often originate not from malice but from systemic gaps in how we fill, collect, enrich, and reuse metadata. And when these metadata flows inform research evaluations, bibliometric dashboards, or even policy decisions, the impact becomes forensic.

A Case of Fictional Affiliation

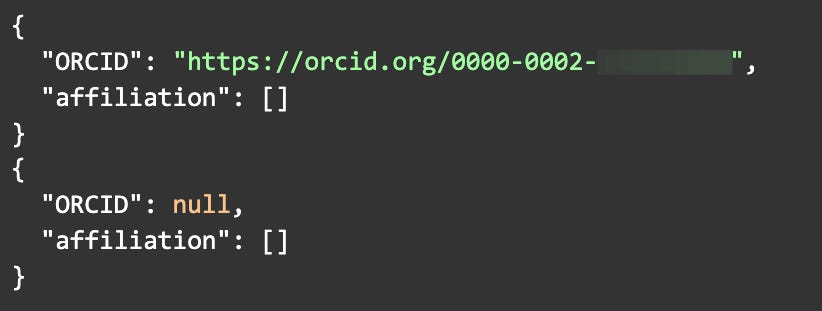

In 2007, a paper titled "Enhanced P2P Services Providing Multimedia Content" was published—and later retracted, in the journal Advances in Multimedia1. On the publisher’s site and in the PDF (primary sources), the authors are all affiliated with Italian institutions. However, Crossref (a secondary source) lists no affiliations2,

and OpenAlex (a tertiary source) attributes the work to researchers allegedly based in Chile, including the University of Chile and the Government of Chile3.

This mismatch demonstrates how some sources, in trying to "fill in" missing data, may inadvertently generate fictional metadata chains, metadata that looks complete but has no foundation in the actual publication.

This is not simply a metadata bug. It’s an institutional misattribution of a retracted article, now incorrectly linked to a public university in another country. In forensic terms, it’s a contamination event, an error in upstream metadata that propagates through the system, compounding reputational and analytical damage.

When Metadata Becomes a Liability (or a Broken Chain of Custody)

Some may argue that metadata can’t be perfect, and that’s true. Several posts from Crossref have addressed this directly4. But precision is not the goal; governance is. Accepting metadata in secondary sources as “good enough” without clear validation pipelines or attribution standards puts researchers and institutions at risk, especially as more decisions rely on large-scale, open bibliographic data.

A useful analogy comes from clinical laboratory traceability: When handling biological samples, every step is logged, from the origin, temperature, and handler to each transformation applied, ensuring a transparent chain of custody. If metadata were treated like lab samples, the lack of affiliation information in a registry like Crossref would flag an incomplete record. The subsequent enrichment by aggregators like OpenAlex would be audited for reliability before being propagated or cited.

But in our current scholarly ecosystem, we often bypass this traceability logic. As a result, errors like this can:

Misrepresent institutional productivity or misconduct history.

Skew bibliometric evaluations are used in funding, ranking, or hiring.

Compromise research integrity dashboards.

Undermine public trust in open infrastructures.

Moreover, these issues are exacerbated when users, often analysts or policymakers, fail to specify the data source level used. Is the information drawn from a primary source (e.g., PDF or repository), a secondary one (e.g., Crossref, DataCite, Web of Science, Scopus), or a tertiary one or aggregator (e.g., OpenAlex, Lens)? Just as empirical research requires transparency in sample origin and method, metadata-driven assessments must clarify the provenance of the records analyzed.

Importantly, this is not a problem caused by OpenAlex, which merely aggregates or tries to fix empty information fields with what is available. The issue's root lies in upstream systems, particularly publishers, that fail to deliver complete and accurate metadata.

Metadata governance, like any governance system, implies responsibility. In this case, that responsibility rests first and foremost with the journals that publish, assign DOIs, and register metadata.

Moving Forward Governance Over Perfection

We cannot expect every metadata record to be flawless. But we can and must create minimum standards and processes for traceability and correction. Initiatives like COMET, FORCE11, Cross-Domain Interoperability Framework and the Open Science Monitor Initiative, among others, have all emphasized the need for metadata that is both machine-actionable and context-aware. The solution is not to abandon ambition but to declare the uncertainty, label the gaps, and document the provenance.

As I learned in the Scholarly Communication Institute FSCI 2024 C05: Forensic Scientometrics course5, metadata is no longer a neutral description layer but part of the research product itself. If we treat metadata carelessly, we risk misrepresenting science as much as through falsified results or manipulated images.

Conclusion: Trust, Traceability, and Source Awareness

Open infrastructures are invaluable. They democratize access, enable large-scale insights, and lower barriers for global participation. But open also means fragile, what enters the system unverified can travel far. And as metadata becomes the foundation for assessment, accountability, and credibility, its flaws are not trivial oversights; they are structural risks.

This is not just a call for better tools. It is a call for clear source declaration and metadata literacy:

Know what kind of source you're using.

Document where metadata comes from.

Demand governance, not just access.

Because when a retracted paper is falsely assigned to an institution that never authored it, open science becomes a liability rather than a safeguard. In a forensic scientometric world, that liability should be traceable, not just explainable.

While this piece focuses on the metadata surrounding journal articles, the same logic applies to repositories, data platforms, aggregators, and services like DataCite. As movements to reform research assessment continue to grow, calling for broader recognition of diverse outputs, we must ensure that the infrastructures supporting those outputs adopt equally rigorous standards of traceability and responsibility. Otherwise, we risk reinforcing the same systemic blind spots we are trying to move away from.

Footnotes

Retraction Notice: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/2007/26070 ↩

Crossref metadata (no affiliations): https://api.crossref.org/works/10.1155/2007/26070 ↩

OpenAlex attribution (includes Chilean institutions): https://api.openalex.org/works/https://doi.org/10.1155/2007/26070 ↩

See Crossref’s blog series on metadata imperfection:

- "The Myth of Perfect Metadata Matching"

- "How Good is Your Matching?"

- "The Anatomy of Metadata Matching" ↩FORCE11 Scholarly Communication Institute Course: C05 – Forensic Scientometrics ↩